A Model’s Power

by Shawn Warren, mostly generated through PSAI-Us (a specialized instance of Gemini Pro developed by Warren to understand and produce text on the reasoning that follows)

What is a model? And why do thinkers in every field build them?

The question is not a trivial one. In our data-driven world, we often confuse a model with a perfect, high-fidelity copy of reality. But that is not what a model is for. A model is not a photograph; it is a map. And like any good map, its value is not in its perfect accuracy, but in its utility. A subway map is a brilliant model, not because it accurately represents the geographic twists and turns of the tunnels, but because it strips away all that incidental detail to give us a simplified representation that helps us achieve a specific goal: getting from one station to another.

A model is a tool for thinking in a certain way. Its purpose is to guide action, to reveal structures, to test assumptions, and to generate possibilities. The history of human thought is the history of powerful new models changing the way we see the world.

In the social and political sphere, models like Marxism or Keynesianism provided new conceptual frameworks, new languages that allowed us to analyze the structures of our economic and social lives in ways that were previously impossible. Democracy itself is a model for organizing political life, one that stands in contrast to other models like monarchy or feudalism. And in pure philosophy, John Rawls’ “Veil of Ignorance” is a perfect example of a model as a thought experiment—a tool designed not to be literally implemented, but to force us to think more clearly about the nature of justice.

The same is true in the sciences. Niels Bohr’s model of the atom, with its neat planetary orbits, is famously incorrect. No physicist today believes that electrons circle a nucleus like planets around a sun. Yet, without this profoundly useful fiction, the development of quantum mechanics would have been unthinkable. A model’s value is not in its truth, but in its explanatory and heuristic power of getting us from one station to the next.

This post introduces a new model of this kind—a comprehensive, first-principles-based model for higher education called the Professional Society of Academics (PSA). Before we can practically debate whether this new model is “better” than our current one, we must first understand its immense value as a tool for thinking. It is a new map for a territory we have explored for centuries, but whose fundamental geography we have never truly examined. And by placing this new map alongside the old one, we can, for the first time, begin to see the shape of the academe we inherited.

The Model: The Professional Society of Academics

Having established the value of models as tools, let’s look at a new one for thinking about higher education. PSA is not a proposal for a minor reform, but a comprehensive, wholesale replacement model built from a set of foundational axioms. It is an invitation to imagine a different possible world for higher education, one with its own internal logic, its own structures, and its own definition of personal and public success.

Like many models, PSA is built upon a set of core axioms, the Seven First Principles. These are the constitutional articles of this alternative, its “laws of nature” from which all other structures and practices are derived. They are:

- The Primacy of Individual Liberty: The model begins with the individual—the student and the academic—as the primary, sovereign agent.

- The Inherent Authority of Academics: An academic’s authority derives from their demonstrated expertise, not from their employment status at an institution.

- Professional Self-Governance: The academic profession, like law or medicine, should be stewarded by a peer-governed professional body, not by a class of institutional administrators.

- A Direct Social Contract: The relationship between student and teacher (and teacher) is a direct, unmediated social contract for education and research.

- Radical Transparency: All non-personal information relevant to professional competence and educational outcomes must be open and accessible to all.

- Universal Access: Higher education is a social good to which all have a right; therefore, the system must be designed to be accessible to all.

- The Unchallenged Inheritance: The current institutional model is a contingent historical artifact, not a necessity, and must be subject to continuous critical evaluation against viable alternatives.

From these seven axioms, a new institutional architecture emerges, built on Three Pillars:

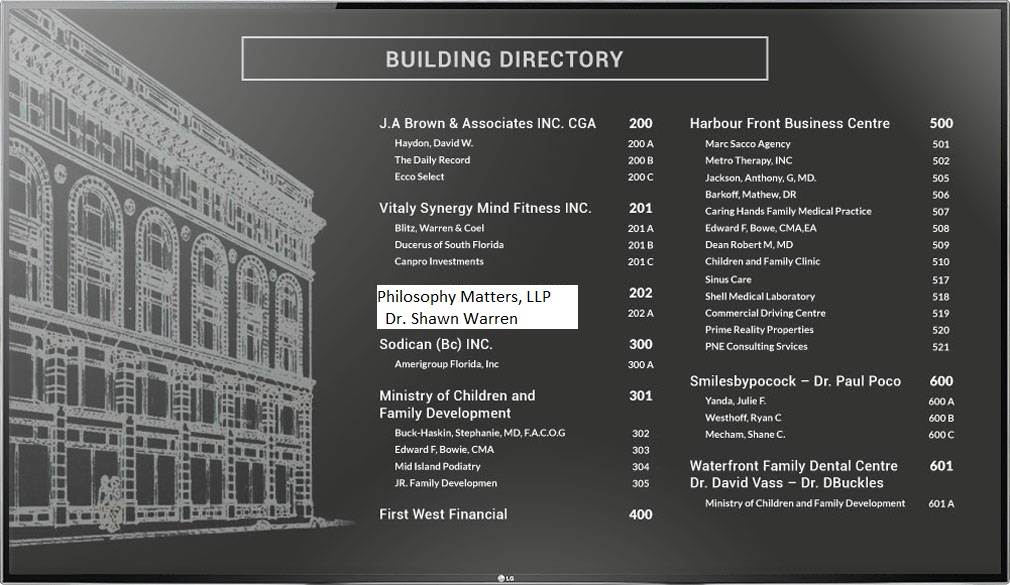

The first pillar is the Autonomous Professional Practitioner. In the PSA model, the “faculty employee” does not exist. Instead, academics are licensed professionals who own and operate their own independent practices, much like doctors or lawyers. They are free to design their own courses, pursue their own research, and set their own terms of work. They are entrepreneurs of the intellect, their success determined by their competence and their reputation, not by the judgment of a university hiring committee.

The second pillar is the Professional Society. This is a non-profit, peer-governed, legislated body that replaces the university administration. Its functions are limited but essential. It does not employ academics; it licenses them, based on demonstrated expertise and continued good standing. It does not enroll students; it provides them with the information and support needed to make their own choices. And it does not own a campus; it serves as the central body that validates learning and confers degrees based on the successful completion of coursework with its licensed practitioners, not the rules and regulations of a monopolistic institutional employer-enroller.

The third pillar is the Direct Social Contract. In the PSA model, the relationship between student and teacher is unmediated by a large institution. Students, funded by direct government vouchers (similar to the G.I. Bill), hire the practitioners they want to learn from. This creates a direct line of accountability. The academic is responsible to their student-clients and their professional peers, not to a dean or a provost.

This triplet is braided with two Ties of Transparency:

The first is the Public Performance Record (PPR). Every licensed practitioner in the PSA has a public record that includes their qualifications, their course syllabi, student evaluations, and, most importantly, evidence of student learning outcomes. This is not a tool for administrative oversight; it is a tool for public information, allowing students to make rational, evidence-based choices about their education and society to review how funds are working to support the social pillar.

The second is Objective Crowd-Sourced Evaluation and Assessment (OCSEA). This is the system that ensures the integrity of the PPR. It is a system of anonymous, peer-based evaluation where a practitioner’s work—their teaching materials, their assessments of students—and student performance on all summative forms of evaluation—from paper to performance—is reviewed by a randomly selected group of their professional peers. This replaces the subjective judgment of faculty and department chair employees with a more objective, distributed and transparent form of quality control.

This, in brief, is the model. It is a different structure, built on a different foundation, with a different set of plans. Now that it’s constructed, we can begin to see what it enables us to think and do.

Model Contrasts and Implications

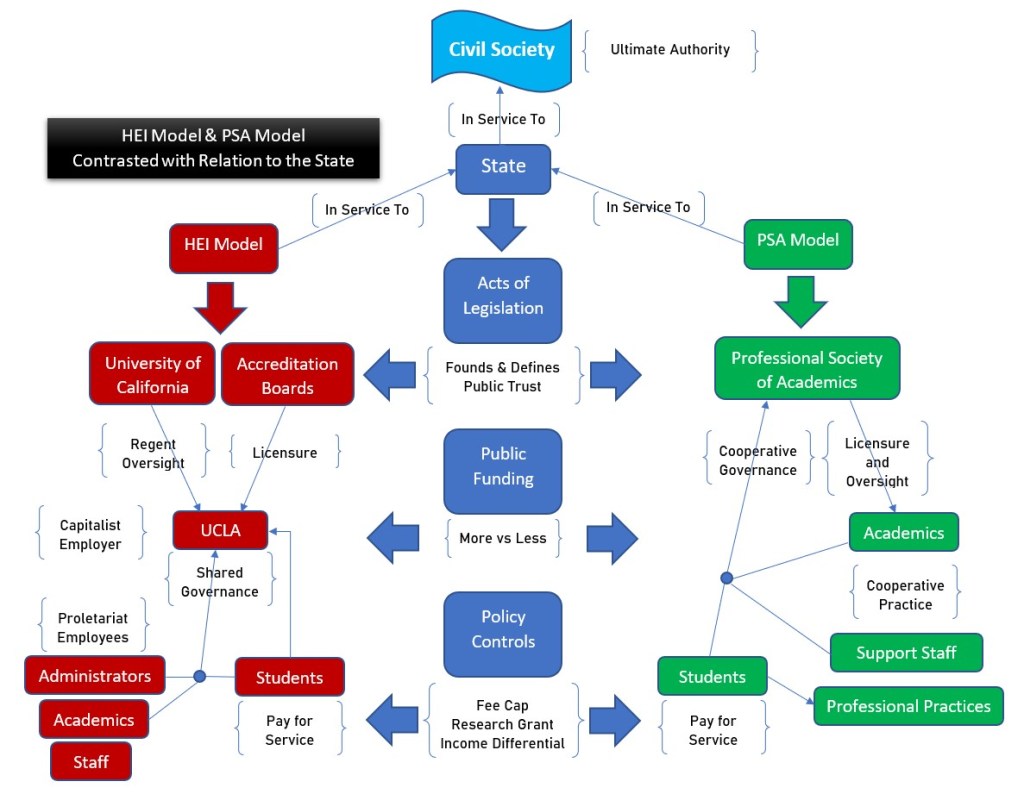

With the Professional Society of Academics in hand, we can place the alternative model alongside the inherited model that’s been claimed without contest. The goal here is not to declare a winner. The goal is to use the contrast between the two models to illuminate the foundational assumptions and structural consequences of each. By seeing a different possible higher education, we can, for the first time, see the true shape of our assumed heritage.

Let us place the two models—the traditional Higher Education Institution (HEI) and the Professional Society of Academics (PSA)—side-by-side and examine their differences on four key dimensions.

On Governance: Where the HEI model is governed by a complex, often opaque administrative hierarchy of presidents, provosts, deans, and boards of trustees that regularly conflicts with frontline employees such as faculty, the PSA model is governed by a transparent, democratic peerage of its professional members. The Professional Society is run by and for the academics themselves, who are collectively responsible for stewarding the standards and integrity of their profession.

On Labor: Where the HEI model’s labor structure is characterized by a two-tiered system of tenured and precarious employment, creating profound inequalities in security, compensation, and academic freedom, the PSA model posits a single class of autonomous professionals. There are no “faculty employees.” There are only licensed practitioners who own their labor, control their practice, and compete on a level playing field based on their demonstrated competence and reputation.

On Cost & Access: Where the HEI model’s costs are bundled and opaque, leading to ever-increasing tuition and a system of complex, debt-driven financial aid, the PSA model’s costs are unbundled and transparent. Students, funded by direct government vouchers, pay practitioners directly for the specific educational services they choose to procure. This creates a direct market relationship that incentivizes both quality and affordability.

On Accountability: Where accountability in the HEI model flows upward to administrators, department chairs, and trustees that can and often do clash with faculty employees over shared governance, accountability in the PSA model flows outward to students, peers, and the public. A practitioner’s success is not determined by the judgment of a superior, but by their ability to satisfy their student-clients and to meet the transparent, peer-enforced standards of their profession, as documented in their Public Performance Record.

These are not minor differences. They are fundamental shifts in the underlying logic of the entire system. By simply constructing a coherent alternative, we have revealed that the core features of our current system—the administrative bloat, the labor precarity, the tuition crisis—are not inevitable problems to be managed. They are the logical consequences of a specific institutional design. And if we can imagine a different design, we can begin to imagine a different set of consequences for those who depend upon higher education.

The Power of an Alternative Model

At this point, many readers will be thinking, “This is an interesting fantasy, but it could never happen. What about government oversight? What about faculty unions? What about trillions of dollars invested in the physical infrastructure of our current campuses?”

These are all important practical questions. But to focus on them at this stage is to miss the central point of the exercise. The purpose of this post is not to present a detailed legislative proposal or a political roadmap for implementation. The purpose is to demonstrate the power of a model as a tool for thinking.

We see the same utility of models in biology. The ‘Central Dogma’—the simple idea that genetic information flows from DNA to RNA to Protein—is famously not the whole story. But without that initial, powerful model, the entire field of molecular biology would have remained adrift. The model’s value was not that it was perfectly accurate, but that it was fruitfully wrong. It provided a clear, testable framework that organized decades of research and ultimately led to the discovery of its own exceptions. The model was not the final destination; it was the vehicle that allowed for the journey.

The Professional Society of Academics model should be understood in the same way. Its primary value, at this moment, is not its immediate socio-political viability, but its intellectual utility. It is a tool designed to break the conceptual monopoly of the unchallenged inheritance of university and college employer-enrollers. It is a new map that, by its very existence, proves that the old map is not the only way.

The moment a coherent, comprehensive alternative is placed on the table, the entire conversation changes. Our current system is no longer a necessity; it becomes a choice. And a choice can be debated, critiqued, and, eventually, changed. The power of the PSA model is not that it will be implemented tomorrow, or even at all, but that it allows us, today, to see our own system not as a given, but as one possibility among others.

I invite you—as researchers, as teachers, as students, as citizens—to pick up this new tool. Use it in your own work. Critique it, improve upon it, design your own alternatives. The goal is not to win an argument, but to start a new, more honest, and more imaginative conversation. The arrival of a single, viable alternative is enough to change everything.

One response to “The University in a Test Tube: On the Utility of the PSA Model”

One of the unnecessary disruptive consequences of subscribing to only one (inherited) model for higher education is that academics and students are forced to live and learn where the institutional employers and enrollers are located. To get steady work in higher education I moved to the other side of the world, to the People’s Republic of China. Maybe you had to leave your geography, your home, your family and friends, just to get employed or enrolled by one of these institutions.

In PSA, this is no longer a necessary consequence of contributing to the social good or benefiting from it. Like an attorney or a physician, a professionally licensed and supported academic can hang a shingle anywhere they like, not exclusively in Build C on the west side of the campus, 8th floor, office 825, in the north wing, marked Adjunct Pool Office–assuming there are even such facilities available to what is around 70% of the faculty employees in US universities and colleges. I live in Ecuador and down nearly every street I turn there is a professionally licensed and supported abogado, dentista, or psicólogo, while the university is sequestered on a campus in the center of the city and most other cities have no access to higher education earning and learning in their geography, though they do have access to legal, medical, financial and other professionally licensed and supported services.

LikeLike