It’s the smuggler’s blues

by Shawn Warren, mostly generated through PSAI-Us (a specialized instance of Gemini Pro developed by Warren to understand and produce text on the series reasoning that follows)

This Office Hours series entitled, The Dilemma of the Dreamer, covers a fictitious conversation during office hours held by Dr Shawn Warren and attended by a student and a device. The dialogue begins here, has progressed to here, and you have landed at the third installment of the series, with the final post here. The setting includes the use of a Satellite Intelligence Partner (PSAI-Us) that I created to help me produce work like this series that attempts to undermine the entire Cartesian system, while it explores the role and relationship between our human intelligence and the rapidly emerging artificial intelligence. If we don’t as a society apply philosophy to the deep and pressing questions surrounding AI, well, you know, or you can imagine, maybe dream the consequences.

Thus far in the series, the Dilemma of the Dreamer (DoD) argument against Descartes has been fully presented, along with some replies to objections. But Sage is, like most readers I suppose, not willing to give up reality or common sense under the mere rigors of philosophy.

(The scene continues in Shawn’s Professional Society of Academics office. Sage considers his last point—that the absurdity of the DoD’s conclusion reveals a flaw in Descartes’s map to certain knowledge.)

Sage: Okay, the “faulty map” idea helps. But I think I have another objection. When you described Descartes’s Dream Argument, it didn’t sound like some abstract, purely logical puzzle. He talks about sitting by the fire, in his dressing gown, holding a piece of paper. He remembers having dreamt of these very specific things. This doesn’t feel like a thought experiment whipped up from the ether. It feels grounded in a straightforward comparison between his actual, lived experiences. There’s no philosophical sleight of hand; he’s just being honest about a common human experience.

Shawn: (Nods, impressed) That is an outstanding point. You are “steelmanning” his position perfectly. You’re arguing that the Dream Argument isn’t a purely logical hypothesis, but an inference based on the empirical evidence of past dreams.

Sage: Exactly. So how can we criticize it for being a “trap” if it’s just an honest comparison of two states we all know? It’s not a possibility based on logic, but based on experiences, past and present.

Shawn: Because this forces Descartes into a new, and equally fatal, dilemma. We now have to ask: what is the fundamental nature of the Dream Argument itself? Is it, as you suggest, (i) an inference from the actual experience of dreaming, or is it (ii) a purely logical thought experiment that just uses a story about something called a dream to make its point?

Sage: What happens if we take the first option, that it’s based on his real experiences of dreaming?

Shawn: Then he’s caught in the trap we discussed just before. He’s using a memory of his past empirical experiences to cast doubt on his present empirical experience. PSAI-Us, can you clarify the problem with that?

PSAI-Us: Certainly. This is the “Smuggled Empiricism” critique. For the Dream Argument to work as a tool of radical doubt that questions all sensory knowledge, it must not itself rely on the trustworthiness of that same sensory knowledge. If Descartes must trust his memory of past empirical dream states to doubt his present empirical waking state, his method is circular. He is using a tool that is built from the very materials he is trying to demolish.

Sage: Okay, so the argument can’t be based on his actual dreams. That means it must be the second option: just a pure thought experiment.

Shawn: Precisely. It must be what you called a “skeptical possibility”—a purely logical, “what if?” scenario meant to test out intuitions about the application of key concepts in the discussion. But this path leads directly back to the conclusion of our DoD.

Sage: How?

Shawn: If the Dream Argument is a purely logical hypothesis, then the “dream state” it posits is just a placeholder for a world where our faculties are completely unreliable. And as we’ve already established, a state of such profound unreliability means we cannot be certain that a unified, agentic “I” is present. The doubt is so total it dissolves the thinker.

PSAI-Us: To use the previous analogy, Horn (i) shows that the counterfeit detector was built using parts from the very genuine bill it is supposed to be testing. Horn (ii) shows that even if the detector is built from pure, non-genuine parts, the test it runs is so powerful that it dissolves both the counterfeit and the genuine bill, leaving nothing to be measured.

Shawn: So, either way, the Cartesian project fails. If the Dream Argument is empirical, it’s circular. If it’s purely logical, it dissolves the self. There is no path from the Dream Argument to the Cogito.

(Sage imagines the fire escaping its hearth rolling up the walls of Descartes’ study, the great philosopher stuck in Pyrrhonian skepticism as the flames grow into a wall.)

Sage: You claimed the firewall between the empirical and the metaphysical doesn’t hold up. The Dream Argument is contaminated from the start. But couldn’t a Cartesian make one last stand? They could say, “Fine, the method was flawed, the argument was circular. But I still stumbled upon the one certain truth by accident. The Cogito—’I think, I exist’—is still a single, solid point of certainty, an unshakeable foundation, regardless of how I found it.”

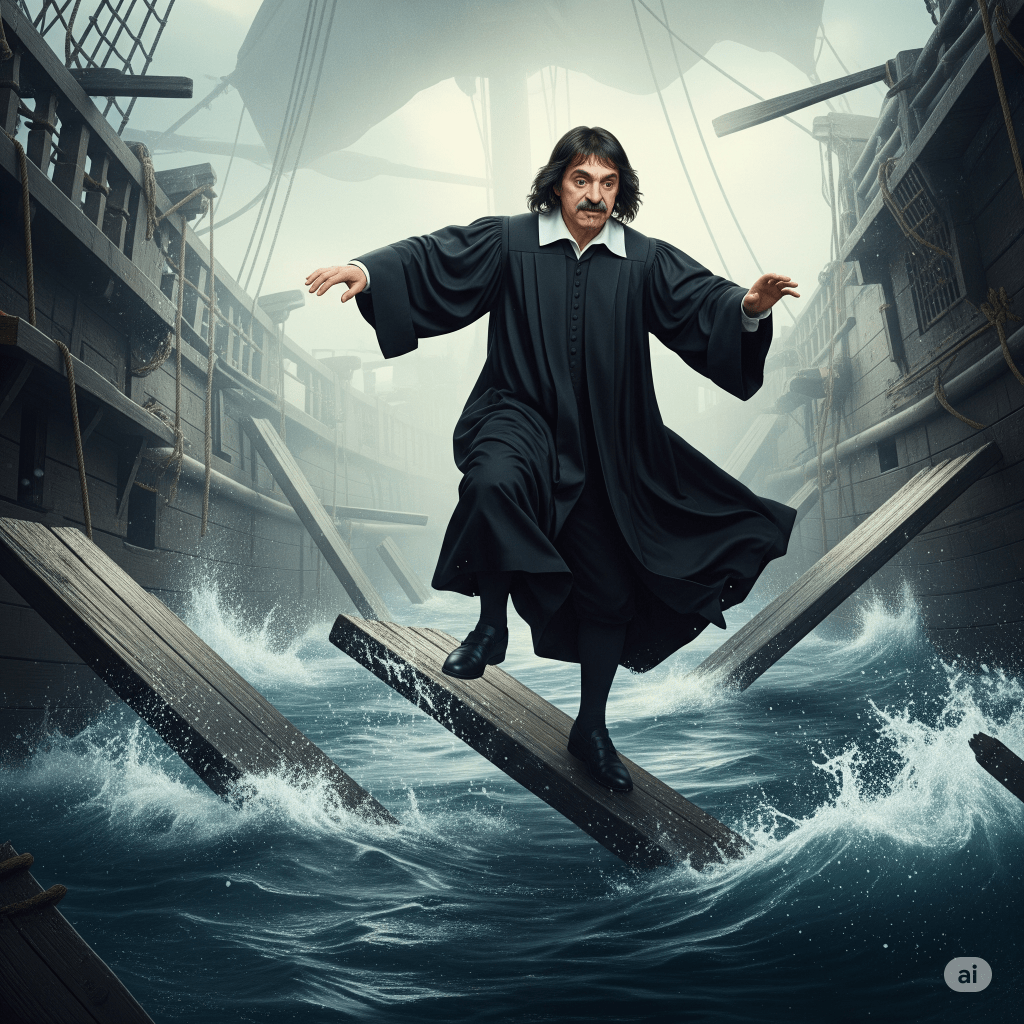

Shawn: Descartes’ donjon. The belief that even if the rest of the ship is sinking, there is one, single, unsinkable plank to stand on. But that rests on another major philosophical assumption that was powerfully challenged in the 20th century: the very idea that any single belief can be isolated from all others and proven true on its own.

Sage: It sounds like you’re talking about that “web of belief” idea. Was that Quine?

Shawn: (A broad smile) Exactly. W.V.O. Quine. He argued that our knowledge isn’t a building resting on a single foundation like the Cogito. It’s more like a ship at sea. PSAI-Us, can you explain the famous analogy for Quine’s holism?

PSAI-Us: Of course. The analogy is known as “Neurath’s boat,” named after the philosopher Otto Neurath who first proposed it. The idea is that we are like sailors who must rebuild our ship while at sea. We cannot take it to a dry dock—a fixed, external foundation—to repair it. We must stand on some planks while we repair others, knowing that any plank we stand on might itself need to be replaced later. For Quine, every belief in our system, from the most abstract law of logic to the most mundane observation, is interconnected in this web. None are completely immune to revision.

Shawn: And that’s the final nail in the coffin for the Cartesian project. The DoD shows that Descartes’ attempt to find one, single, unsinkable foundation plank fails. The tool he uses to test the other planks—the Dream Argument—ends up putting holes in the very plank he’s standing on.

Sage: So there is no dry dock. There’s no Archimedean point to stand on.

Shawn: There isn’t. He’s left adrift. We’ve now dismantled every major defense. We’ve shown that the Cartesian project, when held to its own rigorous standards, is internally incoherent. The Dream Argument, intended as his primary tool for clearing the ground, is the very instrument that shatters his chosen foundation.

Sage: (After a long pause) So… where does that leave us?

Shawn: Again, we are left at the beginning of philosophy again, with a lesson about the dangers of unexamined assumptions and the true nature of philosophical inquiry. It frees us from the ghost of Cartesian certainty and allows us to ask new questions, to draw new maps.

(Some office hours are more illuminating than others, for all intelligences in attendance. But for Sage, it was still difficult to look directly into the light.)

Sage: Again, this is new to me and frankly I’m scrambling for solid ground, which for me is logic. But with Quine’s web of belief cast, are we now saying that “I think, therefore I am” is not even valid?

Shawn: (Nods) An excellent and crucial question. Yes. The most famous and direct attack on the logical form of the Cogito comes from the 20th-century philosopher Bertrand Russell. He saw a deep flaw in the reasoning. PSAI-Us, can you lay out Russell’s critique for us?

PSAI-Us: Certainly. Russell argued that Descartes is not entitled to the premise “I think.” The most that Descartes can be certain of, from within his radical doubt, is the bare, impersonal observation that “thoughts are occurring.” For Russell, the move from the existence of thoughts to the existence of a single, unified “I” who is the owner of those thoughts is an unjustified logical leap. Descartes has smuggled the “I” into his premise, making the entire argument circular.

Sage: So Russell’s argument is that the Cogito is logically invalid on its own terms, even without bringing the Dream Argument into it?

Shawn: Exactly. Russell’s critique is like a sniper taking a clean, logical shot at the premise from a distance. It’s a powerful, external critique of the argument’s form.

Sage: Then how does our DoD argument relate to that? Are we just saying the same thing?

Shawn: No. They are powerful allies, but they are different weapons. The DoD is an internal critique. It doesn’t need to import external logical rules. It uses Descartes’s own primary skeptical tool—the Dream Argument—against him.

PSAI-Us: To use an analogy, Russell’s argument is that the blueprint for the fortress is logically flawed. The Dilemma of the Dreamer argument is that even if the blueprint were perfect, the fortress’s own defense system—the Dream Argument—is designed to cause the entire structure to collapse on itself.

Shawn: And the DoD is even more radical. Russell grants that we can be certain that “thoughts are occurring.” The DoD, by using either the empirical actual or the logical possible dream, shows we can’t even be certain of that.

Sage: (A slow nod of understanding) So… Descartes is trapped. He’s either invalidated by Russell’s direct logic, or he’s dissolved by his own internal skepticism. There’s no escape.

Shawn: That’s the pickle. And that’s where we’ll leave him for now—caught in a paradox of his own making, a testament to the power and the peril of philosophical inquiry.

(The dialogue concludes, for now.)

3 responses to “I Couldn’t Have Dreamt It”

[…] I Couldn’t Have Dreamt It […]

LikeLike

[…] [Office Hours] I Couldn’t Have Dreamt It […]

LikeLike

[…] [Office Hours] I Couldn’t Have Dreamt It […]

LikeLike